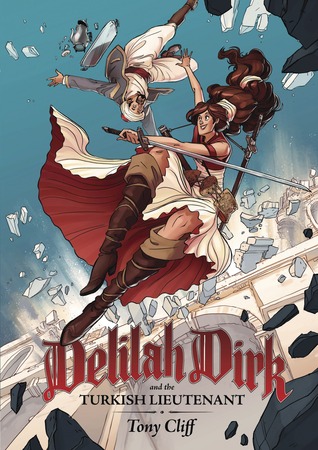

You guys probably know by now that I'm able to stretch just about anything to make it a good fit for Austen in August, if it's something I want to cover. I mean, last year I reviewed on of the Matter of Magic books because it was set in Regency England (and had a pretty cover...); that was all the excuse I needed. Who needs Kevin Bacon when you've got Six Degrees of Jane Austen? Delilah Dirk and the Turkish Leiutenant is one of those books that isn't a direct retelling, and it probably isn't even all that Austen-y in scope, but dammit, I think it looks really good and I wanna include it! Fortunately for me, turns out Delilah Dirk's author, Tony Cliff, is a bonafide Janeite. Once again, I win the internets.

Check out Tony's post below, about how he discovered Jane Austen (and then discovered she's kinda awesome), and then make sure to stop back by later today for a chance to win a copy of Delilah Dirk and the Turkish Leiutenant!

Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey is one of my favourite novels, much to my own surprise. Not just my favourite Jane Austen novel, but one of my favourite novels all-told. This feels as though I am making a private confession, which is an impressive step in terms of personal growth. Previously, this would have felt like an embarrassing admission. Not too long ago, reading the full text of that book would not have even been conceivable to me.

The work of Jane Austen carries baggage, at least stereotypically. I will avoid specifying what were my notions of this stereotype so as to skirt any potential offence to the reader who, at any rate, would know how foolish it is to organize one’s life based on stereotypes and perceived notions. After all, this is one of the lessons to be learned from more than one of Austen’s stories. Nevertheless, I was a man of five and twenty years when I first discovered that I may be required to engage with Austen’s work as a matter of necessity. I resisted, partially because of the stigma – Jane Austen books are reading material for ladies, not gentlemen of substance, and there is a certain saccharine quality to the exaggeratedly romantic peripheral elements that have grown around the six original stories like ju-jube barnacles – but also because at the time the language was borderline impenetrable to me.

However, I had also developed a desire to write and illustrate a story set in the early 19th century involving at least one English female character. I was well through the process of creating the first graphic novel featuring this setting and this character when I began to write additional stories. I was enticed by the idea of contrasting an adventurous female character with some of the typical female characters described in various stories of Austen’s. There was one another roadblock I wasn’t expecting, though. After giving one of these stories to a trusted friend, I asked her for her thoughts. She was kind and helpful, and among her comments she pointed out that I had described my character wearing what is effectively Victorian-era dress. Considering that the story was to take place in the neighbourhood of 1810 and the Victorian era didn’t begin until roughly the 1830s, I ought to be clothing my characters in Regency-period dress. As I had already established the time period in the first book, and as I desired to exploit the events of the Napoleonic Wars, I was tied to the Regency period.

For the female characters, that meant Empire waistlines.

The reader, most likely being familiar with Austen’s work and period, will understand what is an Empire waistline. For those who do not, please take this opportunity to engage with an internet search tool to discover a wealth of images and description. During the Regency period, popular dress for women in England often featured a waistline which sat very high – most often just below the bust. The reader may recall this look experiencing a brief return to fashionable taste (and perhaps this is where the author betrays some of his supposed stereotypical masculinity) during the mid-2000s. The fabric of a dress would often fall straight and loose from the high Empire waistline. Cut poorly, this style of dress had the effect of making even the slightest of figures appear as though she were with child. Upon initially encountering Regency dress, I believed it to be the lowest of low points within the history of fashion, having none of the typical, reliable appeal of the Victorian era’s emphasis on hourglass figures for women.

I didn’t care much for men’s dress during the period, either, but little could compare with my distaste for the Empire waistline.

Nevertheless, discipline in the name of historical accuracy demanded that I embrace the fashion of my chosen setting. It was difficult, a great personal Mt. Everest, but I figured that since I desired to play fast-and-loose with historical detail elsewhere in the work, it made sense that buttressing the accuracy in areas such as costume would heighten the believability of the less-believable elements. So I begrudgingly began watching film adaptations of Austen’s work.

I encountered great difficulty. The language was difficult to parse, even paired with excellent performances from the actors. The subtleties of the relationships and the specific social norms were completely lost on me. If the reader is familiar with Austen’s work, she will recognize how fatal this is to the enjoyment of said work, for each of Austen’s works revolves around the complications of human interaction within the rigid social structures of the times. The conflict, drama, and humour all spring from how Austen’s characters would have been expected to behave, and without a knowledge of the unwritten rules which these characters were ducking and diving to survive within, much of the value of the stories is lost. Having not discovered this fact until much later, I simply believed Pride and Prejudice to be capricious and incomparably dull.

I kept chipping away at the Austen mine, though, as I selfishly believed it would provide useful material for my own work. It would be fun to create an exaggeratedly adventuresome, tomboyish character to play against this Austen world, so I kept digging for understanding. I found it in useful little companion guides written expressly to assist modern readers in comprehending the standards of England in the early 1800s.

Then something exciting happened. I imagine it was a combination of my having been primed properly with preparatory study and it being a particularly well-produced adaptation, but when I watched the 2009 Romola Garai four-part BBC Emma, I found it legitimately enjoyable. Outside of its usefulness as research material, I was enjoying Emma for what it was. Some of its appeal might also be attributed to it sharing aesthetics and cutesy sensibilities with Pushing Daisies, a personal favourite TV series. Whatever opened the doors for me, I had crossed the threshold and was now happily enjoying Austen.

The books were still challenging, though. I recall barely struggling through a few chapters of an annotated Pride and Prejudice. Perhaps the annotations distracted from the “flow” of the text. Perhaps I still wasn’t conversant in the manner of the language.

Enticed by a plot description that seemed dissimilar to what I expected from a Jane Austen novel and by the notion that the book itself “parodied” novels – which at the time were generally thought of the way soap operas now are thought of relative to prime-time TV – I acquired a copy of Northanger Abbey. Without annotations.

Similar to what I experienced with Emma, I’m unsure exactly why I found myself able to enjoy Northanger Abbey when similar work had been so challenging to engage with. Perhaps I had once more achieved enough fluency in the relevant prerequisite material to allow me to swim where previously I would have drowned. Whatever the reason, I found Austen’s voice to be charming, observant, full of humour, and not a little sardonic – a definite contrast to the sappy, romantic qualities I was expecting. Her turns of phrase, which previously would have left me scratching my head (“I assure you I did not above half like coming away”) now seemed amusing and colourful. I was especially surprised to discover her self-conscious quasi-breaking of the fourth wall, such as this passage directly referencing the fact that the reader is aware how many pages are left in the book and that events are likely to conclude (spoiler alert) happily:

“The anxiety, which in this state of their attachment must be the portion of Henry and Catherine, and of all who loved either, as to its final event, can hardly extend, I fear, to the bosom of my readers, who will see in the tell-tale compression of the pages before them, that we are all hastening together to perfect felicity.”

Additionally, this line one page later particularly pleases me with its inclusive hand-waving flippancy:

“Any further definition of his merits must be unnecessary; the most charming young man in the world is instantly before the imagination of us all.”

I had generally enjoyed the book up to that point. I haven’t even mentioned how modern and specifically observed some of Austen’s characters seem, once the reader is able to penetrate the language barrier. This level of casual self-awareness from the narrator, though, so in contrast with the rigid social behaviours expected by the story’s setting and characters, sealed the proverbial deal, and I found myself a genuine Jane Austen fan.

|

| Click the pic to be taken to the Austen in August Main Page! Thanks to faestock & inadesign for the images used to create this button. |

To be fair to an empire waistline, it's is fantastic for hiding a podgy belly, like you say, you can't be sure what is going on under there :)

ReplyDeleteThis is an interesting piece. I am impressed that you managed to persevere since you disliked it so much at first. I didn't find it too bad at first read, but it may have helped that I am British, so although we don't talk like that we probably talk more like that than they do in other places and also that I've always quite liked older books, from children's books onwards so the older style of language wasn't such an obstacle. Once you get used to the language you start to notice Austen's humour and her wry observations. For me, they are books that you notice more to appreciate every time you read them.

Excellent points about her narration, which is often quite cheeky but rarely noted as one of her books' qualities.

ReplyDeleteEnjoyable post, Tony! I, too, am glad you persevered until Jane Austen became old habit. I think you discovered what many still don't see that these novels are not necessarily romances. Not that they are devoid of romance just that the focus many times is on wit and humor to prove a point about humanity. Northanger Abbey is definitely one of her wittiest pieces for certain.

ReplyDeleteGreat Post!!! These books have it all. Yes I love the bits of romance but its the overall truth of peoples natures that keep me reading. These books translate so well to modern day retellings because of the fundamentals. Stripe everything away and you still have peoples basic natures whether, vain, generous, evil, kind or loving its all there.

ReplyDelete